Названия стран и национальностей на английском языке

Одна из первых тем, которую можно встретить в учебниках и книгах по английскому – это названия стран и национальностей на английском языке. Поэтому и блог «English, Sir» не будет исключением. Итак, давайте рассмотрим, как образуются национальности, и как можно обращаться к жителям разных стран.

Начнем с первого и важного правила.

Прилагательные и страны в английском языке

Начнем с примера.

- He speaks Russian. (Он говорит по-русски);

- He likes Russian food. (Он любит русскую еду);

- He is Russian. (Он русский);

- He is from Russia. (Он из России).

Как видите, от названия страны можно образовать три слова, обозначающих – язык, национальность и прилагательное (для описания чего-либо, например, еда, фильм, одежда и т.п).

В данном примере прилагательное от названия страны образовано при помощи суффикса – ian. Тема не зря начата с изучения прилагательных. Большинство национальностей и названия языка совпадает с прилагательным, образованным от названия страны. Но есть и исключения. Обо всем этом будет рассказано ниже.

Давайте рассмотрим основные суффиксы для образования прилагательных от названия стран.

Сразу стоит отметить, что нет единого правила образования. Прилагательные, языки и национальности нужно просто запоминать. В статье будут представлены наиболее употребительные страны, которые очень часто бывают на слуху. Их вполне будет достаточно для начального уровня.

Для лучшего запоминания, суффиксы разделы по географическому положению стран.

Суффикс «ian»

Прилагательные с суффиксом «ian» образуются для многих стран Южной Америки, Африки, Австралии и Океании, страны Европы и Канада. Если слово заканчивается на «ia», то добавляется только «n».

- Canada — Canadian

- Brazil — Brazilian

- Norway — Norwegian

- Russia — Russian

- Belgium — Belgian

- Egypt — Egyptian

- Argentina — Argentinian

- Australia — Australian

- Austria — Austrian

- Belarus — Belarusian

- Colombia — Colombian

- Italy — Italian

Суффикс «an»

Суффикс «an» характерен для Северной Америки, Африки и несколько стран Южной Америки.

Если название страны оканчивается на «A», то добавляется только «N». Если название оканчивается на другую гласную – добавляется «AN».

- Mexico – Mexican

- America — American

- Kenya — Kenyan

- Chile – Chilean

- Germany — German

- Venezuela – Venezuelan

Суффикс «ese»

Суффикс «ese» используется для большинства стран Азии. Также для стран Африки и Южной Америки.

- China – Chinese

- Vietnam – Vietnamese

- Japan – Japanese

- Sudan – Sudanese

- Taiwan – Taiwanese

- Lebanon – Lebanese

- Portugal — Portuguese

Суффикс «ish»

С суффиксом «ish» образуются в основном страны Европы

- Britain – British

- Scotland – Scottish

- Ireland – Irish

- Wales – Welsh

- Poland – Polish

- Turkey – Turkish

- Finland — Finnish

- Spain — Spanish

Суффикс «i»

Суффикс «i» характерен для большинства исламских стран.

- Iraq – Iraqi

- Pakistan – Pakistani

- Thailand – Thai

- Kuwait – Kuwaiti

И конечно не обойтись без исключений. Есть прилагательные, для которых нет определенного правила образования.

- France – French

- Greece – Greek

- Switzerland – Swiss

- The Netherlands – Dutch

- Denmark — Danish

- Poland — Polish

Национальности и жители стран на английском

Мы начали изучение с прилагательных не зря. Большинство национальностей совпадает с формой прилагательных, которые мы рассмотрели выше. А вот образование отдельных жителей и нации в целом имеет некоторые особенности.

Определенный артикль плюс прилагательное

Всех жителей страны можно обозначить как добавлением окончания «s(es)», так и определенного артикля «the» к прилагательному.

Если прилагательное оканчивается на «ian», «an», «i», то для обозначения всех представителей нации добавляется окончание «S». Определенный артикль в данном случае не употребляется.

- Austrian — Austrians

- American — Americans

- Iraqi — Iraqis

- Thai — Thais

Для большинства остальных прилагательных требуется определенный артикль «the». Как правило, для прилагательных, оканчивающихся на «sh», «ss», «ch», «ese».

- The Chinese

- The French

- the Japanese

- the Spanish

- the Dutch

Однако, если по контексту подразумевается определенная группа людей одной нации, то артикль the употребляется в обоих случаях.

I think the Americans will win this game. (Думаю Американцы выиграют эту игру) — определенная группа (команда), как представители страны.

Прилагательное плюс people

Всю нацию в целом можно также образовать добавлением к прилагательному слова people. В данном случае возможно как употребление с определенным артиклем, так и без него.

- (the) Russian people- русские

- (the) Italian people – итальянцы

Как обычно не обойтись без исключений.

Некоторые нации не соответствуют прилагательному. Для них используются специальные существительные. В таком случае обязательно используется артикль «the».

- Finland – the Finns

- Great Britain – the British

- Poland – the Poles

- Scotland – the Scots

- Spain – the Spaniards

- Sweden – the Swedes

Выше мы рассмотрели всех жителей страны. Но как обозначить одного представителя?

Здесь также ничего сложного. Чтобы отметить только одного жителя, к единственному числу прилагательного или существительного добавляется неопределенный артикль a/an.

Для того, чтобы уточнить пол жителя определенной страны, к единственному числу добавляются слова man, woman, boy, girl

- A Russian woman

- An American boy

Об английском с любовью

Словообразование. Суффиксы “-IAN ( –AN, –N)”.

Продолжаем заниматься очень важной темой – законами построения слов. Напоминаю, что слова, относящиеся к главным частям речи ( существительные, прилагательные, глаголы и наречия) могут иметь аффиксы, то есть суффиксы и префиксы. Проще говоря все “длинные” слова имеют фиксированные окончания и приставки. Если вы не знаете значения слова и хотите посмотреть его в словаре, то префиксы и суффиксы надо обязательно убирать, так как может оказаться, что вы вспомнили значение основы. Тогда и всё слово станет понятным. А если вы не знаете значение основы, тогда надо искать в словаре основу, а не всё “длинное” слово целиком.

Но чтобы убрать суффикс, надо знать его “в лицо”, то есть знать и понимать его значение. Каждая главная часть речи имеет свои собственные суффиксы, то есть, зная, как выглядит суффикс, уже понятно, существительное это или глагол и т.д. Но есть несколько суффиксов, которые образуют слова в разных частях речи, например, суффиксы “-ian (-an,-n)” могут быть и у существительных, и у прилагательных одновременно. Я называю такие суффиксы «двуликими». Однако перепутать по смыслу слова с такими суффиксами невозможно, так как по месту в предложении легко отличить существительное от прилагательного.

Суффиксы образуют слова, которые имеют отношение к:

а) искусству или направлению в науке.

AGRONOMICS = агрономия + IAN = AGRARIAN = крупный землевладелец, аграрий; сторонник аграрных реформ;

ARITHMETIC = арифметика, счёт + IAN = ARITHMETICIAN = арифметик;

BARBARITY = варварство, жестокость, грубость, бесчеловечность + IAN = BARBARIAN = варвар;

COMEDY — комедия + IAN = COMEDIAN = автор комедий, актёр- комик;

DIALECTICS = диалектика + IAN = DIALECTICIAN = диалектик;

GEOMETRY = геометрия + IAN = GEOMETRICIAN = геометр;

GRAMMAR = грамматика + IAN = GRAMMARIAN =грамматик;

HISTORY = история + IAN = HISTORIAN = историк;

LOGIC = логика + IAN = LOGICIAN = логик;

MAGIC = магия, волшебство + IAN = MAGICIAN = волшебник. чародей, заклинатель, фокусник.

MATHEMATICS = математика + IAN = MATHEMATICIAN = математик.

MUSIC = музыка + IAN = MUSICIAN = музыкант, композитор;

OPTICS = оптика + IAN = OPTICIAN = оптик;

PATRIARCHY = патриархат + IAN = PATRICIAN = патриций;

PEDESTRIAN = пешеход, участник соревнований по спортивной ходьбе;

PHONETICS = фонетика + IAN + PHONETICIAN = фонетист;

PHYSIC = медицина + IAN = PHYSICIAN = врач, доктор, целитель;

POLITICS = политика + IAN = POLITICIAN = политик, государственный деятель.

PRACTICE = практика, действие, применение + IAN = PRACTICIAN = практик;

PROLETARIAT = пролетариат + IAN = PROLETARIAN = пролетарий;

STATISTICS = статистика + IAN = STATISTICIAN = статистик;

TACTICS = тактика + IAN = TACTICIAN = тактик; ловкий , умелый организатор.

TECHNICS = техника, технические науки + IAN = TECHNICIAN = человек, хорошо знакомый с техникой своего дела;

THEOLOGY = богословие + IAN = THEOLOGIAN =богослов;

TRAGEDY = трагедия + IAN = TRAGEDIAN = трагик, трагический актёр;

VEGETABLE = овощ, овощи + VEGETARIAN = вегетарианец;

VULGARISM = вульгарность, вульгарное выражение + IAN = VULGARIAN = вульгарный, невоспитанный человек;

б) месту проживания или национальности.

Mexico (n) = Мексика + an = Mexican = (n) мексиканец, мексиканка. (adj)мексиканский.

Russia (n) = Россия + n = Russian = (n) русский, россиянин. (adj) русский.

Canada (n) = Канада + ian = Canadian = (n) канадец, канадка. (adj) канадский.

Egypt (n) = Египет + ian = Egyptian = (n) египтянин, египтянка. (adj) египетский.

Norway (n) = Норвегия + ian = Norwegian = (n) норвежец, норвежка. (adj)норвежский.

Paris (n) = Париж + ian = Parisian = (n) парижанин, парижанка. (adj) парижский.

America (n) = Америка + n = American = (n) американец, американка. (adj)американский.

Linglish.net

Where English meets Linguistics

So many nationality suffixes

After posting my other article So many negative prefixes , I received very positive feedback and many readers apparently found the article interesting and useful. Indeed, these little affixes (prefixes and suffixes) can be puzzling when they are similar in meaning but nevertheless non-interchangeable. That makes people ask why they are what they are: is there a subtle rule beneath all the messy superficial distribution, or things just happen by chance?

Not long ago, a friend asked me whether there are rules governing the usage of those suffixes of nationality, such as —ese, —ian and —ish. I thought about it for a while, then I remembered that years ago I read a post on the Internet, saying that —ese is a derogatory ending used only on those countries that the western world thought to be inferior, so we have adjectives like Chinese, Vietnamese and Burmese. After all, many of the Asian countries do form their adjectives in —ese. But I had doubts, don’t the westerners just love Japanese stuff? And why Korean, Indian, Malaysian and Indonesian then? So I decided to look for the answer myself.

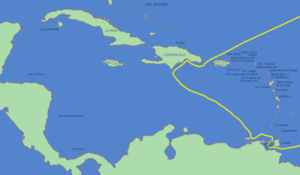

I fetched a list of nationality adjectives from NationMaster.com, then I started to color the world map according to the suffixes used to form their respective nationality adjectives. Finally I got this map:

Suffixes of Nationality

From the list, I find 8 major suffixes, they are:

- -ian (Italian, Norwegian)

- -ean (Chilean, Korean)

- -an (American, Mexican)

- -ese (Chinese, Japanese)

- -er (Icelander, New Zealander)

- -ic (Icelandic, Greenlandic)

- -ish (English, Irish)

- -i (Iraqi, Pakistani)

Looking at the map, we can probably notice some distributive patterns right away. For instance, —ish is mainly used for European nations, —i is for nations in the Middle East, —ic and —er seem to occur only after the word —land, but the others seem to be more random.

Not satisfied with the mere geographical picture, I decided to trace the histories of these suffixes.

| Suffix | Origin |

| -ian | Latin |

| -ean | Latin |

| -an | Latin |

| -ese | Latin → Italian |

| -er | Latin → Germanic |

| -ic | Latin → Germanic |

| -ish | Germanic |

| -i | Arabic |

-ian / -ean / -an

It should not be surprising to find out that —ian, —an and —ean actually have a common origin. In fact, the suffix —ia is frequently used in Latin to name places, thus giving birth to names like Romania, Bulgaria and Australia, and —ea and —a are two other grammatical suffixes used on Latin nouns. The final —n is an adjectival suffix that turns a noun into an adjective. Hence, adjectives that end in —ian, —ean, or —an were either borrowed directly from Latin, or modelled after Latin in English. They are the standard suffixes now in English. The distribution of them follows a rule that is rather neat and tidy. Basically it goes as follows:

- If the place name ends in —ea or a silent —e, then use —ean;

- If the place name ends in a vowel, then use —an;

- Otherwise, use —ian.

As you have probably noticed, there are some exceptions or complications, but let us not be concerned about that here. After all, the general picture is clear and unambiguous.

Let us now turn to the controversial suffix —ese. You could well say that there does not seem to be a pattern geographically. Countries using —ese are scattered everywhere in Asia, Africa, South America, and we also have Portugal in Europe! But my attention turns to Italian when I give this suffix some more thought.

In Italian, —ese is a much more common suffix of nationality than in English. Words that use —ese in Italian but not in English include danese (Danish), finlandese (Finnish), francese (French), inglese (English) and islandese (Icelandic). In fact, —ese (from Latin —ēnsis) is the next most common suffix after the Latin triplet —ian/-ean/-an.

The Third Voyage of Christopher Columbus

It turns out that words ending in —ese in English actually come from Italian. Recalling that Marco Polo and other Italian traders were the first Europeans to reach the Far East, it is therefore no surprise that many Asian countries use —ese. In addition, the countries using —ese in South America are all very close to where Christopher Columbus, himself an Italian, first landed on the continent. But of course, why some countries in Africa and the Americas use the Italian suffix, while others use French or Spanish suffixes is a result of their long and complicated colonial histories.

-er / -ic

Both —er and —ic are originally Latin suffixes which later entered the Germanic languages and subsequently English. Among the two hundred countries in the world, —er and —ic are used only after the words land and island, both of which are Germanic in origin. The suffix —er is used on nouns to denote persons of a certain place of origin, while —ic is used to form adjectives with the meaning of “having some characteristics of”. Therefore, Icelander is normally used to denote a person from Iceland (i.e. a noun), whereas Icelandic is used when it is used as an adjective.

This is a native Germanic suffix with the sense of “belonging to”. Since English has been much influenced by French and Latin, the suffix is not as productive as it used to be. However, in other Germanic languages, such as German, its usage is far more common. Nationalities which use —ish in German (-isch) but not in English include Italienisch (Italian), Chinesisch (Chinese), Isländisch (Icelandic) and Irakisch (Iraqi). Its Germanic origin explains why nationalities that use —ish are all in Europe, and belong to Germanic nations around Germany and Scandinavia. This is even clearer if you consider two more facts:

- The word German does not end in —ish, because the united nation of Germany did not exist until relatively recently. The word German comes from a Latin word referring to the people in that region.

- Both French (from Frencisc) and Dutch (from Diutisc) in fact contain the suffix —ish, although in both cases, the suffix has been fused with the base to form a new, irregular adjective.

The suffix —i, with the meaning of “belonging to”, comes from Arabic. This explains why almost all countries that use —i are Islamic and/or use Arabic as one of the major languages. Geographically, the center of this group of nations is in the Middle East, and extends to Central Asia to the north, and to East Africa to the south. A notable exception in this area is Iran, which had a long history of contact with the West before they gradually converted to Islam.

Summary

After seeing the distribution of the suffixes of nationality on a world map, and studying the origins of these suffixes, I think we should be reasonably convinced that the choice of suffix is not entirely a matter of chance or taste. Instead, there are historical and linguistic factors which determine why one suffix is used for a certain nationality but another suffix for a second one.

English is a Germanic language, its native suffix for nationality is —ish, which accounts for the names of nearby nationalities. But before English had gone global and applied its suffix to other nationalities, it was influenced by Latin and French. The default suffix of nationality used in the language was replaced by the Latinate —ian/-ean/-an, so more recently coined nationalities made use of them instead. Later, the contact between Italy and the Far East, together with the European colonization of Africa and South America, brought in some nationalities ending in —ese. Then, Islamic countries near the Middle East retained their Arabic —i when their names entered English. Lastly, a few places that end in —land or Island make use of the suffixes —er/-ic.

On second thought, the whole picture is just that simple.

| Benin | Beninese |

| Bhutan | Bhutanese |

| Burma | Burmese |

| China | Chinese |

| Congo | Congolese |

| East Timor | Timorese |

| Faroe Islands | Faroese |

| Gabon | Gabonese |

| Guyana | Guyanese |

| Japan | Japanese |

| Lebanon | Lebanese |

| Malta | Maltese |

| Marshall Islands | Marshallese |

| Nepal | Nepalese |

| Portugal | Portuguese |

| San Marino | Sammarinese |

| Senegal | Senegalese |

| Sudan | Sudanese |

| Suriname | Surinamese |

| Taiwan | Taiwanese |

| Togo | Togolese |

| Vietnam | Vietnamese |

| Albania | Albanian |

| Algeria | Algerian |

| Armenia | Armenian |

| Australia | Australian |

| Austria | Austrian |

| Bahamas, The | Bahamian |

| Barbados | Barbadian |

| Belarus | Belarusian |

| Belgium | Belgian |

| Bermuda | Bermudian |

| Bolivia | Bolivian |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Bosnian and Herzegovinian |

| Brazil | Brazilian |

| Brunei | Bruneian |

| Bulgaria | Bulgarian |

| Burundi | Burundian |

| Cambodia | Cambodian |

| Cameroon | Cameroonian |

| Canada | Canadian |

| Cayman Islands | Caymanian |

| Chad | Chadian |

| Colombia | Colombian |

| Croatia | Croatian |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Ivoirian |

| Djibouti | Djiboutian |

| Ecuador | Ecuadorian |

| Egypt | Egyptian |

| Estonia | Estonian |

| Ethiopia | Ethiopian |

| Fiji | Fijian |

| French Polynesia | French Polynesian |

| Gambia, The | Gambian |

| Georgia | Georgian |

| Ghana | Ghanaian |

| Grenada | Grenadian |

| Guam | Guamanian |

| Haiti | Haitian |

| Hungary | Hungarian |

| India | Indian |

| Indonesia | Indonesian |

| Iran | Iranian |

| Italy | Italian |

| Jordan | Jordanian |

| Laos | Laotian |

| Latvia | Latvian |

| Liberia | Liberian |

| Lithuania | Lithuanian |

| Macedonia, Republic of | Macedonian |

| Malawi | Malawian |

| Malaysia | Malaysian |

| Maldives | Maldivian |

| Mali | Malian |

| Mauritania | Mauritanian |

| Mauritius | Mauritian |

| Micronesia, Federated States of | Micronesian |

| Mongolia | Mongolian |

| Montserrat | Montserratian |

| Namibia | Namibian |

| New Caledonia | New Caledonian |

| Nigeria | Nigerian |

| Norway | Norwegian |

| Panama | Panamanian |

| Peru | Peruvian |

| Romania | Romanian |

| Russia | Russian |

| Saint Helena | Saint Helenian |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | Kittitian and Nevisian |

| Saint Lucia | Saint Lucian |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | Saint Vincentian |

| Saudi Arabia | Saudi Arabian |

| Serbia and Montenegro | Serbian |

| Slovenia | Slovenian |

| Syria | Syrian |

| Tanzania | Tanzanian |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Trinidadian and Tobagonian |

| Tunisia | Tunisian |

| Ukraine | Ukrainian |

| Wallis and Futuna | Wallisian |

| Zambia | Zambian |

| Antilles | Antillean |

| Belize | Belizean |

| Cape Verde | Cape Verdean |

| Chile | Chilean |

| Equatorial Guinea | Equatorial Guinean |

| Eritrea | Eritrean |

| Guinea | Guinean |

| Guinea-Bissau | Guinean |

| Korea | Korean |

| Niue | Niuean |

| Papua New Guinea | Papua New Guinean |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | Sao Tomean |

| Sierra Leone | Sierra Leonean |

| Singapore | Singaporean |

| Zimbabwe | Zimbabwean |

| American Samoa | American Samoan |

| Andorra | Andorran |

| Angola | Angolan |

| Anguilla | Anguillan |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Antiguan |

| Aruba | Aruban |

| Central African Republic | Central African |

| Comoros | Comoran |

| Costa Rica | Costa Rican |

| Cuba | Cuban |

| Dominica | Dominican |

| El Salvador | Salvadoran |

| Germany | German |

| Guatemala | Guatemalan |

| Honduras | Honduran |

| Jamaica | Jamaican |

| Kenya | Kenyan |

| Libya | Libyan |

| Mayotte | Mahoran |

| Mexico | Mexican |

| Moldova | Moldovan |

| Morocco | Moroccan |

| Mozambique | Mozambican |

| Nauru | Nauruan |

| Nicaragua | Nicaraguan |

| Palau | Palauan |

| Paraguay | Paraguayan |

| Puerto Rico | Puerto Rican |

| Rwanda | Rwandan |

| Samoa | Samoan |

| South Africa | South African |

| Sri Lanka | Sri Lankan |

| Tokelau | Tokelauan |

| Tonga | Tongan |

| Tuvalu | Tuvaluan |

| Uganda | Ugandan |

| United States of America | American |

| Uruguay | Uruguayan |

| Venezuela | Venezuelan |

| Wallis and Futuna | Futunan |

| Denmark | Danish |

| Finland | Finnish |

| Ireland | Irish |

| Poland | Polish |

| Scotland | Scotish |

| Spain | Spanish |

| Sweden | Swedish |

| Turkey | Turkish |

| United Kingdom | British |

| Afghanistan | Afghanistani |

| Azerbaijan | Azerbaijani |

| Bahrain | Bahraini |

| Bangladesh | Bangladeshi |

| Iraq | Iraqi |

| Israel | Israeli |

| Kazakhstan | Kazakhstani |

| Kuwait | Kuwaiti |

| Kyrgyzstan | Kyrgyzstani |

| Oman | Omani |

| Pakistan | Pakistani |

| Qatar | Qatari |

| Saudi Arabia | Saudi |

| Somalia | Somali |

| Tajikistan | Tajikistani |

| Turkmenistan | Turkmenistani |

| United Arab Emirates | Emirati |

| Uzbekistan | Uzbekistani |

| Yemen | Yemeni |

| Greenland | Greenlandic |

| Iceland | Icelandic |

| British Virgin Islands | British Virgin Islander |

| Christmas Island | Christmas Islander |

| Cocos (Keeling) Islands | Cocos Islander |

| Cook Islands | Cook Islander |

| Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) | Falkland Islander |

| Guernsey | Channel Islander |

| Jersey | Channel Islander |

| New Zealand | New Zealander |

| Norfolk Island | Norfolk Islander |

| Pitcairn Islands | Pitcairn Islander |

| Solomon Islands | Solomon Islander |

| Virgin Islands | Virgin Islander |

| Afghanistan | Afghan |

| Argentina | Argentine |

| Botswana | Motswana |

| Burkina Faso | Burkinabe |

| Cyprus | Cypriot |

| Czech Republic | Czech |

| France | French |

| Gibraltar | Gibraltar |

| Greece | Greek |

| Kiribati | I-Kiribati |

| Laos | Lao |

| Lesotho | Basotho |

| Liechtenstein | Liechtenstein |

| Luxembourg | Luxembourg |

| Madagascar | Malagasy |

| Man, Isle of | Manx |

| Monaco | Monegasque |

| Netherlands | Dutch |

| Niger | Nigerien |

| Philippines | Philippine |

| Seychelles | Seychellois |

| Slovakia | Slovak |

| Swaziland | Swazi |

| Switzerland | Swiss |

| Thailand | Thai |

| Vanuatu | Ni-Vanuatu |

| Western Sahara | Sahrawi |

Related Articles

33 Responses to “So many nationality suffixes”

As a writer I have to say thank you so much for this gem of an article. Also,conducting research for grammatical confirmation is usually boring. Yet I rather enjoyed reading this one. Kudos on making typically boring subject matter interesting.

As for “-er”, linguistics doesn’t limit itself to “it must be a country”. New Yorkers would be quick to point out that their term doesn’t have a -land in there anywhere. Same goes for hoosiers, though their term is weird and shrouded in mystery. Michiganers, Dubliners, Melbourners, Londoners, and more will join in with them.

An interesting exception to the “-i means Arabic” occurs in Illinois with the natives being called Illini after the native american tribe that the state is named for. However, “-i” and “-ee” are very common first nations suffixes for tribes.

Marco Polo called China “Cathay” and the inhabitants “Cathays”. Bzzzt. Good try though.

-ese countries were named in the west by Portuguese traders and settlers.

[…] Extra work: I also found this interesting article about nationality sufixes (ending with -ish -ese- an, etc) and how there isn’t an exact grammar rule for them. You can check it out here: So Many Nationality Suffixes […]

http://oose.ru/slovoobrazovanie-ldquo-dvulikie-rdquo-suffiksyi-suffiksyi-ldquo-ian-ndash-an-ndash-n-rdquo/

http://www.linglish.net/2008/10/22/so-many-nationality-suffixes/